Advanced Guide to Authenticating Fine Chinese Ceramics

China’s ceramic tradition spans thousands of years, producing an unmatched variety of materials, techniques, glazes, motifs, and forms. From utilitarian wares to the most refined court pieces, ceramics became a cornerstone of trade, cultural identity, and artistic expression—passed down through generations and coveted by collectors across the world.

The Foundation for New Collectors

The breadth of Chinese ceramic production can seem overwhelming at first: dynasties, kiln systems, motifs, reign marks, and glaze formulas. But with curiosity and focus, anyone can learn to recognize and appreciate great ceramic works. Books are a great start. Recommended beginner references include:

- Chinese Ceramics by He Li (Asian Art Museum)

- A Dictionary of Chinese Ceramics and Underglaze Blue and Red by Wang Qingzheng

- Ming Ceramics in the British Museum by Jessica Harrison-Hall

- Chinese Ceramics: Selected Articles from Orientations 1982–1998

Start with a specific area of collecting—such as a period, type of ware, or dynasty—and build expertise gradually. Deep knowledge of one or two areas will serve you better than broad, shallow exposure.

The Role of Observation

Your best tool is your eye. Examine as many high-quality examples as possible—both in print and in person. Pay attention to:

- Color (glaze clarity, depth of pigment, variations in underglaze)

- Form (balance, weight, and consistency with standard shapes)

- Motifs and patterns (density, precision, placement)

- Brushwork and execution (line control, flow, proportion)

- Firing and condition (glaze flaws, bubbles, or pooling)

Do not be discouraged by scholarly jargon. While academic and scientific insights are valuable, you do not need a PhD—or fluency in Chinese—to be a serious and informed collector.

Myths About Fakes

There are persistent fears that only a few elite experts can discern real from fake, or that Chinese artisans can replicate any antique with perfect accuracy. These fears are overblown. When compared side by side, modern fakes are rarely convincing to the trained eye:

- They often have inappropriate clay bodies or modern-looking glaze

- Their brushwork lacks rhythm and historical nuance

- The colors may be too stark or dull

- They show signs of artificial aging, such as inconsistent surface wear

Modern replicas rarely match the spirit, materials, or craftsmanship of authentic imperial or period pieces. The mindset and means of the old masters cannot be easily replicated.

Understanding Ceramic Workshop Structure

During the Ming and Qing Dynasties, production involved specialized teams of artisans—sometimes with over 70 distinct steps in a single piece’s creation. The best kilns employed top talent and materials, producing ceramics with meticulous brushwork, excellent form, and balanced color. Even when repeating standard motifs, the quality of execution varied:

- Some artisans painted freely and masterfully

- Others showed stiffness, uneven spacing, or smudging

Collectors must learn to recognize these differences. Two similar vases from the same kiln and period can vary dramatically in value based on precision, balance, and color harmony.

Don’t Obsess Over Minor Deviations

Motif differences—such as extra cloud tendrils, slightly fewer feathers, or variances in foliage—are common. These reflect artistic freedom or kiln variation, not necessarily inauthenticity. However, major inconsistencies (like a dragon with six toes or odd compositional imbalance) can lower value or signal inexperience.

A well-executed, finely painted piece with strong form and pleasing color will retain value regardless of minor motif irregularities.

Variations in Marked Imperial Wares

Even official wares with reign marks can differ substantially. Differences in brush technique, cobalt preparation, firing conditions, and even artistic skill all contribute. Collectors must learn to judge the quality of painting and execution—not just the presence of a mark.

Unfortunately, many of the finest ceramics remain unpublished and out of museums. This knowledge gap makes it easy for dishonest experts to discredit genuine wares for personal gain or market manipulation. Learn what potters of each era were capable of—and judge your pieces accordingly.

The Importance of Color and Form

Color is essential. In blue-and-white porcelain, cobalt tones vary depending on origin, preparation, and firing. The most desirable hues are vivid but soft—neither overly stark nor washed out. Personal preference matters, but harmony and balance always win.

Form also affects value. Between two well-painted vases from the same period, the more elegant silhouette—taller, more refined—will usually be worth more. As with jade, condition is also critical. A flawless, well-preserved object will always command more than a chipped or poorly restored one.

Period vs. Prestige

Earlier blue-and-white pieces from the 14th–15th centuries often carry more value than Qing dynasty pieces, even if they show small flaws. Historical context matters. Qing standards are higher—but so is the supply. Earlier pieces are rarer and offer unique insights into the evolution of Chinese ceramics.

A Word on Rarity and Reputation

Do not be influenced or overvalue Chinese ceramics based on claims of rarity or knowledge of previous owners or sellers. Simply put, no one knows what survives, and values are often inflated for the wrong reasons. Let the object determine its worth—and you, the collector, determine the price.

Compare old auction catalogues from the 1980s with today’s offerings: the quality has risen dramatically. As China continues to open and more collections surface, the standard will rise again. Be selective.

Unusual Colors and Character Pieces

There are also highly collectible wares that exhibit unexpected tones—caused by firing variations or cobalt inconsistencies. Early blue-and-whites, for instance, might appear almost black or purple, and monochromes can vary greatly. These one-of-a-kind anomalies often gain value through uniqueness.

On Firing and Color Development

Firing precision was everything. Even two pieces from the same cobalt batch could differ significantly in tone and vibrancy based on timing alone. One might become dull and washed out, while the other rich and brilliant. These serendipitous outcomes often enhance an object’s charm and collectability.

Final Thoughts

Let the object speak. Train your eye. Trust your judgment. Provenance should not be a crutch. Authenticity is best evaluated through the ceramic itself—its materials, technique, and craftsmanship. Whether you’re collecting early blue-and-whites, doucai wares, or Song monochromes, strive for excellence and let informed passion guide your collection.

Navigate Chinese Masterpieces Site Just Select Pages Below

The Inaugural Ceramics Commissioned by the Emperor in Chinese History: Guaranteed 100% Authenticity from the Northern Song Dynasty's Official Imperial Royal Ru Kiln Porcelain Collection – An Unmatched Provenance of Authenticity.

For All Enquiries Please Contact AGENT : Venizelos G. Gavrilakis, President,VENIS STUDIOS

Email Venizelos@ChineseMasterPieces.com

tel:+971 50 683 5877

I began my collection in the 1970s, and in the 1990s, I focused on acquiring an exceptional array of artworks from private Chinese sources. These sources faced severe persecution for possessing collections that were ancestral heirlooms, predating the Communist era. Among my holdings is the Official Commissioned Imperial Royal Ru Kiln Collection, originating from the collection of Emperor Huizong of the Northern Song Dynasty.

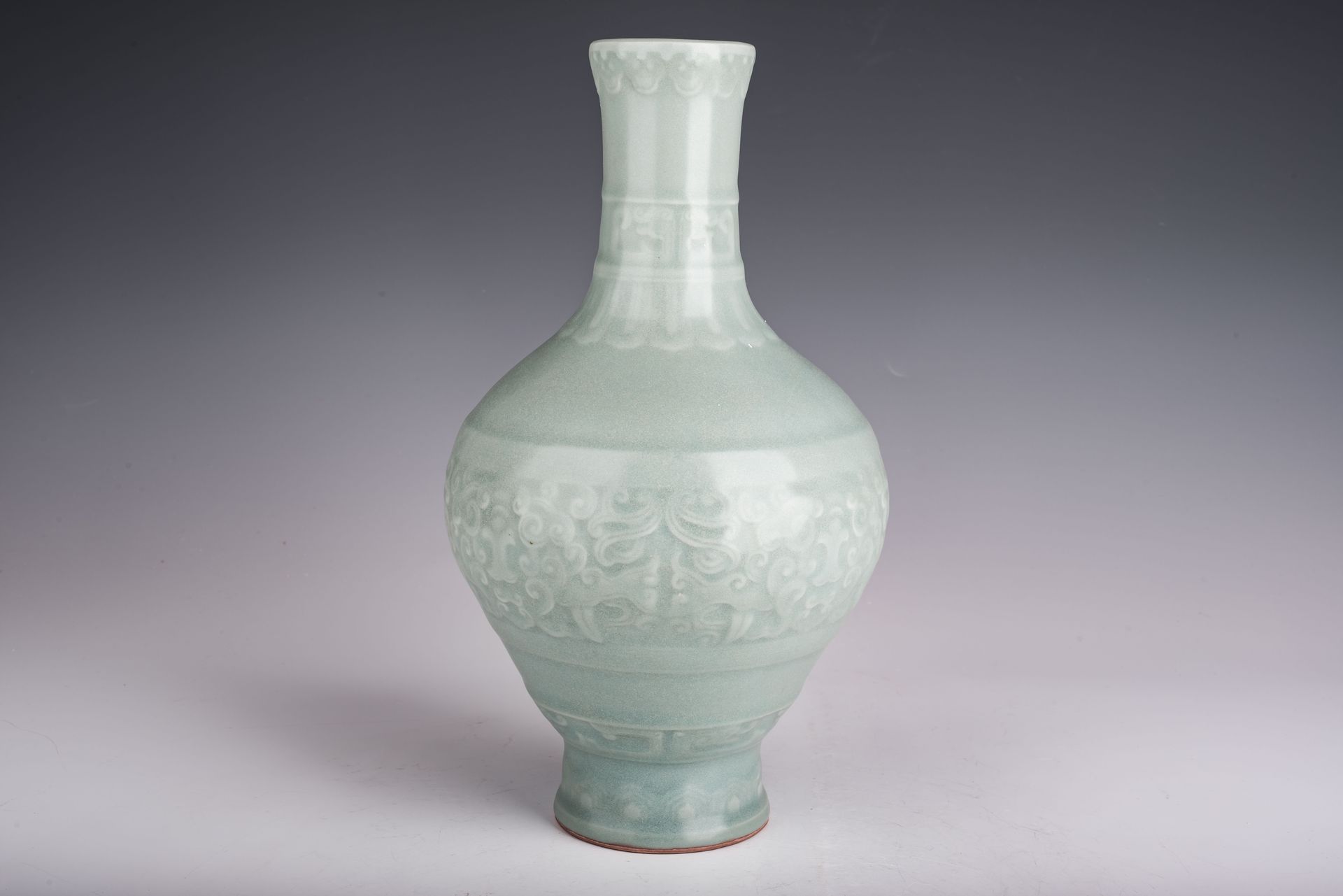

This collection features unique pieces that stand unparalleled in significance, as many of these forms have been previously unseen. The condition of these works is pristine; they are certified 100% authentic, with verifiable characteristics including cuprite and malachite corrosion on the fire-gilded copper bands, which took approximately 900 years to develop. This corrosion is readily observable with the naked eye, as is the crushed agate within the glaze, which can be examined with a 20x loupe. Despite the proliferation of Ru ware across the internet, numerous auction houses continue to erroneously classify these original pieces as fakes, perpetuating misinformation. It is essential to note that only Commissioned Official Royal Imperial Ru wares are genuinely rare. These pieces are not widely available online, and no Royal Imperial Ru wares have ever been offered at auctions. Any skepticism about the authenticity of these wares can be dispelled by recognizing that it would be impossible for any contemporary kiln in China to replicate such masterpieces. Throughout history, the only kiln capable of producing works of this caliber was the Royal Ru Kiln during the Northern Song Dynasty under Emperor Huizong. The second commissioned wares, characterized by unglazed foot rings that were fired flat in the kiln, include the featured Cong vase, which showcases fire-gilded copper bands exhibiting the aforementioned corrosion. The authenticity of these pieces is evident in their cuprite and malachite corrosion, which is readily visible, as well as the crushed agate in the glaze, identifiable with a 20x loupe. Expertise is not a prerequisite for recognizing these facts. It is important to highlight that all second-commissioned wares lack markings and possess an off-white biscuit that turns brownish upon firing. These wares are distinguished by their luxurious, smooth glaze, free from crackle, and display unique features such as fire-gilded copper bands. In my estimation, these second-commissioned wares represent the finest celadon wares and the most significant wares in China’s historical legacy. Emperor Huizong of the Northern Song Dynasty reigned from 1082 to 1135.

Examine and Review the Information Provided Below Thoroughly

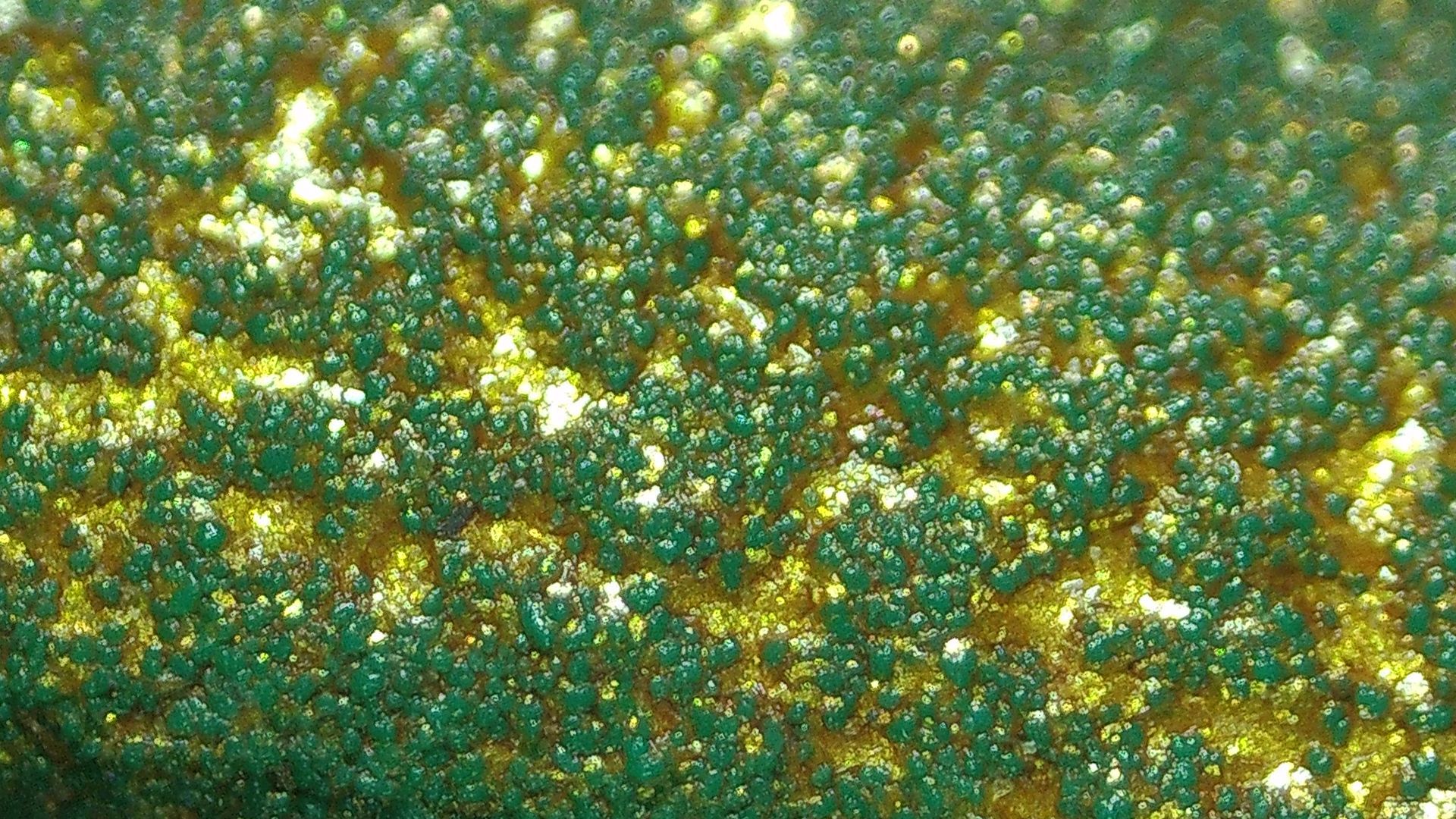

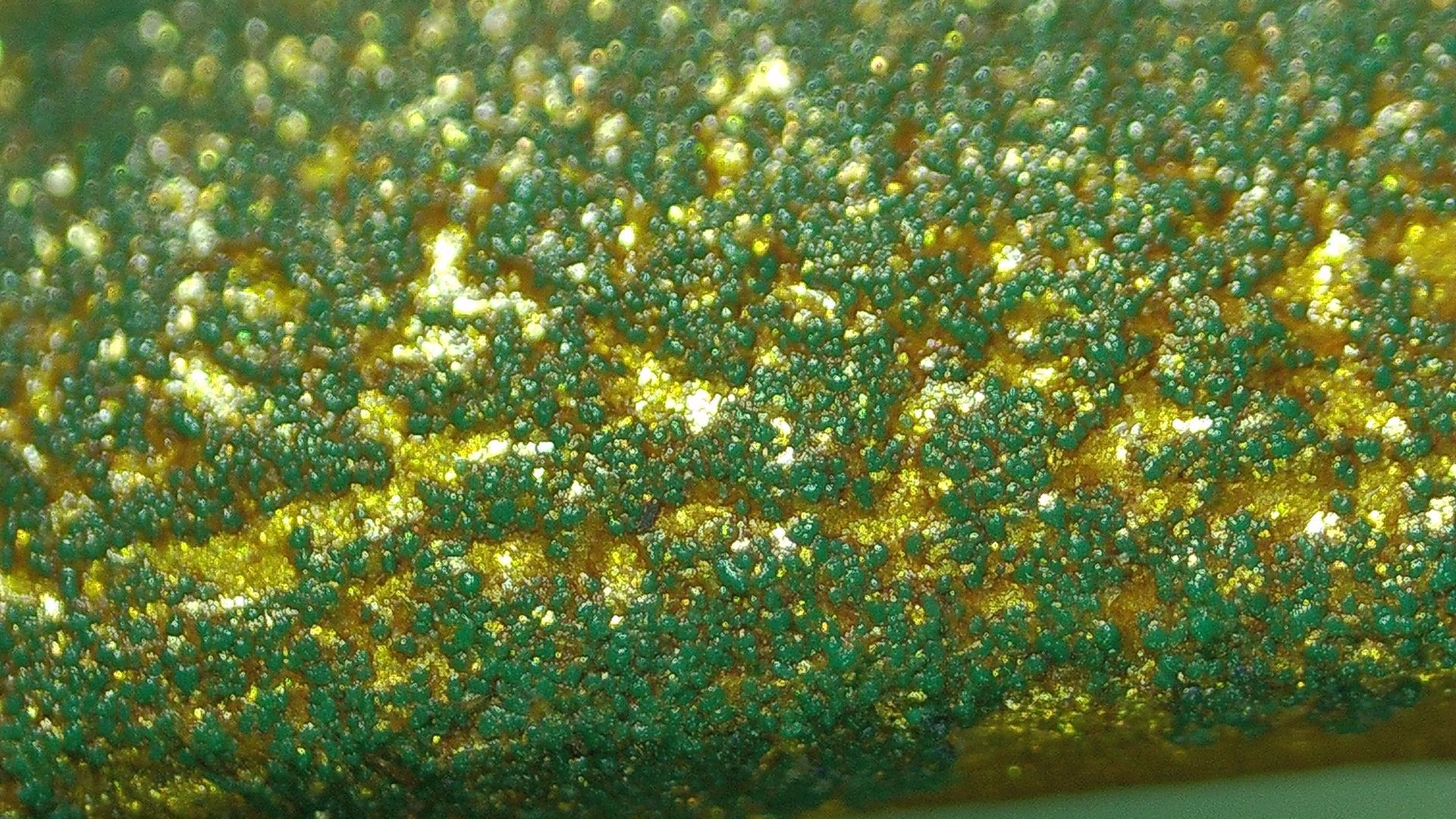

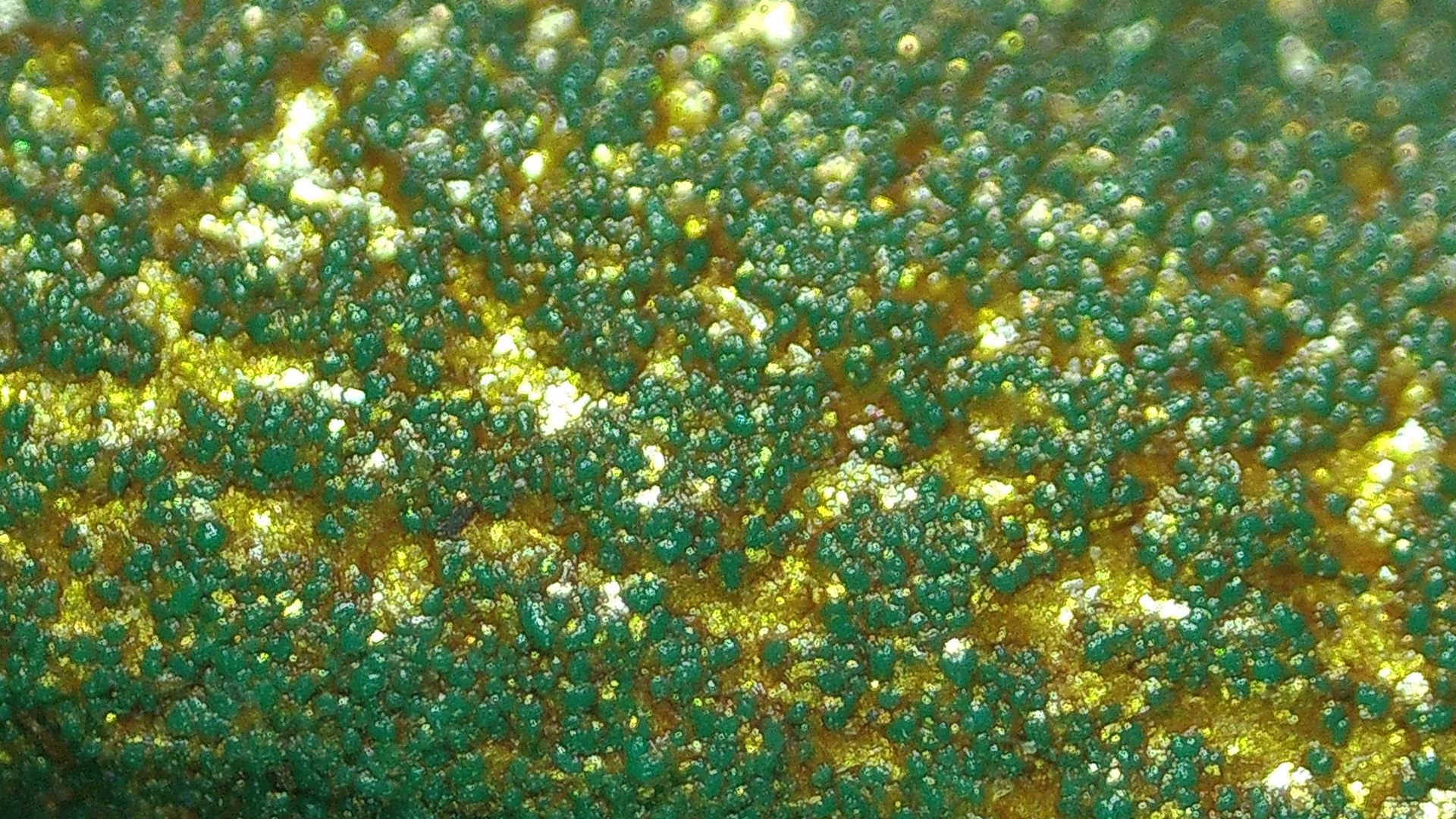

The following series of close-up photographs presents the Cuprite and Malachite corrosion observed on the RU WARE copper fire-gilded bands. It is important to note that fire gilding, a process involving the application of gold and mercury, has not been employed since the mid-19th century due to its associated health risks. The characteristic patina visible on these bands has developed over approximately 900 years, rendering it virtually impossible to replicate artificially (referenced from David Scott's "Copper and Bronze in Art," Chapter 3, page 106). The natural progression from metal to cuprite and subsequently to malachite is complex and challenging to reproduce in a laboratory setting. Indeed, most methodologies for generating artificial green patinas on copper alloys, such as those catalogued by Hughes and Rowe (1982), do not yield malachite formation over a cuprite substrate. As such, the identification of this specific type of corrosion, corroborated by analytical and metallographic investigations, serves as a strong indicator of an artifact's authenticity. Additionally, microscopic images reveal the presence of minute reflective particles of crushed agate incorporated into the RU WARE glaze. Such reflections can also be discerned with a 20x loupe, with further evidence available in the microscopic photographs adjacent to each artifact image. Notably, only the Imperial Ru Wares that were officially commissioned feature crushed agate in their glaze. Pieces sold by auction houses typically do not exhibit this characteristic, as agate was not utilized in merchant wares. The finest merchant wares, equipped with fire-gilded copper bands, were presented as tributes to the Emperor. Meanwhile, flawed merchant wares were sold at reduced prices to the general populace, and those with severe defects were often destroyed. During the reign of Emperor Huizong, significant efforts were made to establish the Ru Kiln as a premier production facility for his personal commissions and those of his court, effectively designating it as the Official Royal Kiln. He specifically mandated the inclusion of rare blue agate in the glazes of all commissioned wares. These official pieces are generally larger and exhibit distinctive styles, forms, and glazes, many of which remain unparalleled in contemporary collections. Archaeological findings have confirmed the location of the Ru Kiln associated with merchant wares predating Emperor Huizong's commissions; however, the site of the Official Royal Ru Kiln has yet to be located.

Following the incursion of the Jin Army into the Northern Song Dynasty, it is believed that many Imperial Royal Kiln artisans migrated southward, with approximately half joining the Imperial Guan Kilns and the other half working at the Longquan Kiln. This migration contributes to the stylistic similarities observed between the renowned second-commissioned Royal Ru Kiln wares and those produced at Longquan. Notably, however, Longquan wares lack the crushed agate incorporation that characterizes the official Ru Wares.

ppjrs

CLICK ON PHOTOS TO ENLARGE

Below are 48 examples of Official Imperial Royal Ru Wares and Tribute Ru Ware Vases

Contact me for Price ppjrs

Understanding "Botryoidal Malachite" Patina

Formation of Fanlike Crystal Needles

Most crystals simply begin to grow using available molecules. This results in discrete crystals whose sizes depend on available material. But malachite is different. It seldom forms discrete crystals of good size. Instead, scientists say, developing malachite crystals “split”, diverging into tiny needles, packed together in a fanlike arrangement.

The fanlike malachite needles grow into tightly bonded spherules, which crowd together and bond, forming a solid mass. When the spherules stop growing and terminate, the top surface is rounded to some degree. The terms “botryoidal” (resembling a cluster of grapes) and “reniform” (kidney-shaped) are used to describe large to small undulating masses of spherules.

Author Bob Jones Holds the Carnegie Mineralogical Award, is a member of the Rockhound Hall of Fame, and has been writing for Rock & Gem since its inception. He lectures about minerals, and has written several books and video scripts.

WATCH

Click On Video Clip Proves Botryoidal Malachite Can't Be Faked! No one has ever faked this Botryoidal malachite patina only happens in nature. This Guaranties Authenticity Of This Imperial Royal Ru Ware Collection

Priceless Past WWW.pricelesspast.com

Link to Full Video https://youtu.be/5O-l6vY0dnc?si=FsHEJdKox0a1p0bH

An Analysis of Royal Imperial Ru Ware Commissioned and Collected by Emperor Huizong of the Song Dynasty During the Northern Song Period. ppjrs

Ancient Treasures: Ru Kiln Secrets Revealed!

Emperor Huizong reigned from 1100 to 1126, during which time he abdicated in favor of his son. He is renowned for his advocacy of Taoism and is celebrated for his exceptional talents in poetry, painting, calligraphy, and music. However, his Northern Song Empire ultimately succumbed to the advancing Jin armies, leading to his capture in 1127. Huizong died in captivity in 1135, having transitioned from the status of the world's wealthiest individual to that of a diminished man. After his death, his extensive collections were meticulously consolidated and preserved in large wooden crates, enduring through time.

Since China's opening in the 1990s, various historical collections have entered the marketplace. Notably, my collection of Imperial Ru ware originates from Emperor Huizong's personal assemblage. During his tenure, he commissioned the Ru Kiln to produce wares specifically for himself and his court, recognizing it as the foremost source of Imperial tribute wares. The tribute wares produced by the Ru Kiln during this era were distinguished by their remarkable quality, often devoid of defects. To further enhance their uniqueness, these wares incorporated a variety of colors and featured fire-gilded bands on the rims, occasionally on the bases. The gilding technique utilized gold and mercury, a method that has not been employed since the mid-1800s due to safety concerns. The intricacies of the fire gilded bands display complex corrosion patterns of cuprite and malachite, natural phenomena that are exceedingly difficult to replicate in laboratory settings. Established research underscores the challenges associated with the transformation from metal to cuprite to malachite, with most synthetic formulas failing to replicate malachite atop cuprite layers, thereby providing validation for the authenticity of such artifacts.

This innovation inspired other kilns to adopt similar techniques, incorporating fire-gilded bands in their tribute wares. Before the Ru Kiln attained its designation as the official Imperial kiln, its production primarily consisted of small wares that exhibited sporadic crackling and spur marks due to the firing process on stilts. Many of these pieces contained imperfections, resulting in the destruction of severely flawed items and the sale of lesser-quality wares to the public at reduced prices. Such flawed wares frequently appear in auctions conducted by Sotheby's and Christie's and are often showcased in museums housing Ru ware collections. Higher-quality pieces were sold at premium prices to affluent merchants. The finest wares were presented as tribute to Emperor Huizong, who received extravagant offerings from various kilns. Recognizing the demand for superior quality wares, Emperor Huizong designated the Ru Kiln as the first official Royal Imperial kiln in China.

His objective was to create wares that were distinctive and specifically intended for himself and his court. He sought pieces that echoed the historical celadon wares, aiming for a jade-like aesthetic reminiscent of Korean Koryo ceramics. After reviewing prototype pieces, he insisted on eliminating spur marks by firing the wares flat in the kiln with unglazed foot rings. Furthermore, he mandated the incorporation of rare blue crushed agate into the glaze, a feature unique to the official Royal Imperial wares commissioned by him. The initially commissioned wares displayed a grayish biscuit that transitioned to brown post-firing, with some pieces bearing inscriptions. These wares featured distinctive crack ice crackles. Emphasizing size and simplicity, these pieces were larger than previous tribute wares and showcased refined forms, such as trumpet-shaped mouths. Despite occasional flaws during the firing process, these Royal Imperial wares were exclusively designated for the Emperor and his court. As the official Imperial kiln, the Ru Kiln's focus was solely on producing wares for the Emperor and his court. Huizong appreciated the intrinsic beauty of these often flawed and simplistic pieces, recognizing their individuality akin to human character.

However, some of his advisors sought more visually appealing wares. Consequently, he tasked the Ru Kiln with creating the most exquisite celadon wares ever produced in China, emphasizing elegance and luxury in design. The second series of official Royal Imperial wares manifested in various celadon hues, adorned with rich glazes that seamlessly integrated rare blue crushed agate. Unlike the initial batch, these wares were meticulously crafted and largely free from prior defects, with exquisite forms and flat-fired unglazed foot rings. Selected special wares featured gilded copper or silver bands, enhancing their opulent appearance. Importantly, all second commissioned official Royal Imperial wares lacked specific markings. It must be emphasized that wares produced before the Ru Kiln’s designation as the official Imperial kiln do not contain agate in their glazes. Certain auction houses and museums mistakenly claim the presence of crushed agate in these earlier wares, fabricating narratives that assert its dissipation during the firing process. This assertion is fundamentally flawed, as agate requires excessively high temperatures for melting—far exceeding the maximum temperatures reached by Song dynasty kilns. Additionally, the practical difficulties associated with crushing agate into a fine powder contribute to the clear visibility of agate traces in authentic Royal Imperial Ru wares.

I have compiled a significant collection of Ru and Ju wares, artifacts that have remained largely concealed since the decline of the Northern Song Dynasty. The Qianlong Emperor's collection predominantly comprised flawed merchant wares developed before the Ru Kiln's establishment as the official Royal Imperial kiln. It is only since the 20th century and the reopening of China that many fine pieces, once obscured from view, have entered the marketplace. This narrative seeks to illuminate the complexities surrounding Ru and Ju Kiln wares in the context of Emperor Huizong's reign. For many years, scholars and collectors have relied on pieces from the Qianlong Emperor's collection; while aesthetically appealing, they do not accurately represent the authentic Royal Imperial Ru and Ju wares commissioned by Huizong for himself and his court.

In the aftermath of the Jin Army's incursion into the Northern Song Dynasty, workers from the Imperial Royal Kiln sought refuge in the southern region, with many likely contributing their skills to the Imperial Guan Kilns, while others joined the Longquan Kiln. Notably, this lineage accounts for the visual similarities observed between certain Longquan pieces and the second commissioned Royal Ru Kiln wares, although the Longquan products lack the characteristic crushed agate present in the latter's glazes.

Please examine all the information, photos, microscopic photos, that prove my conclusion.

The Ru-Wares Represent the First Commissioned Official Imperial Ceramics within China's Historical Context.

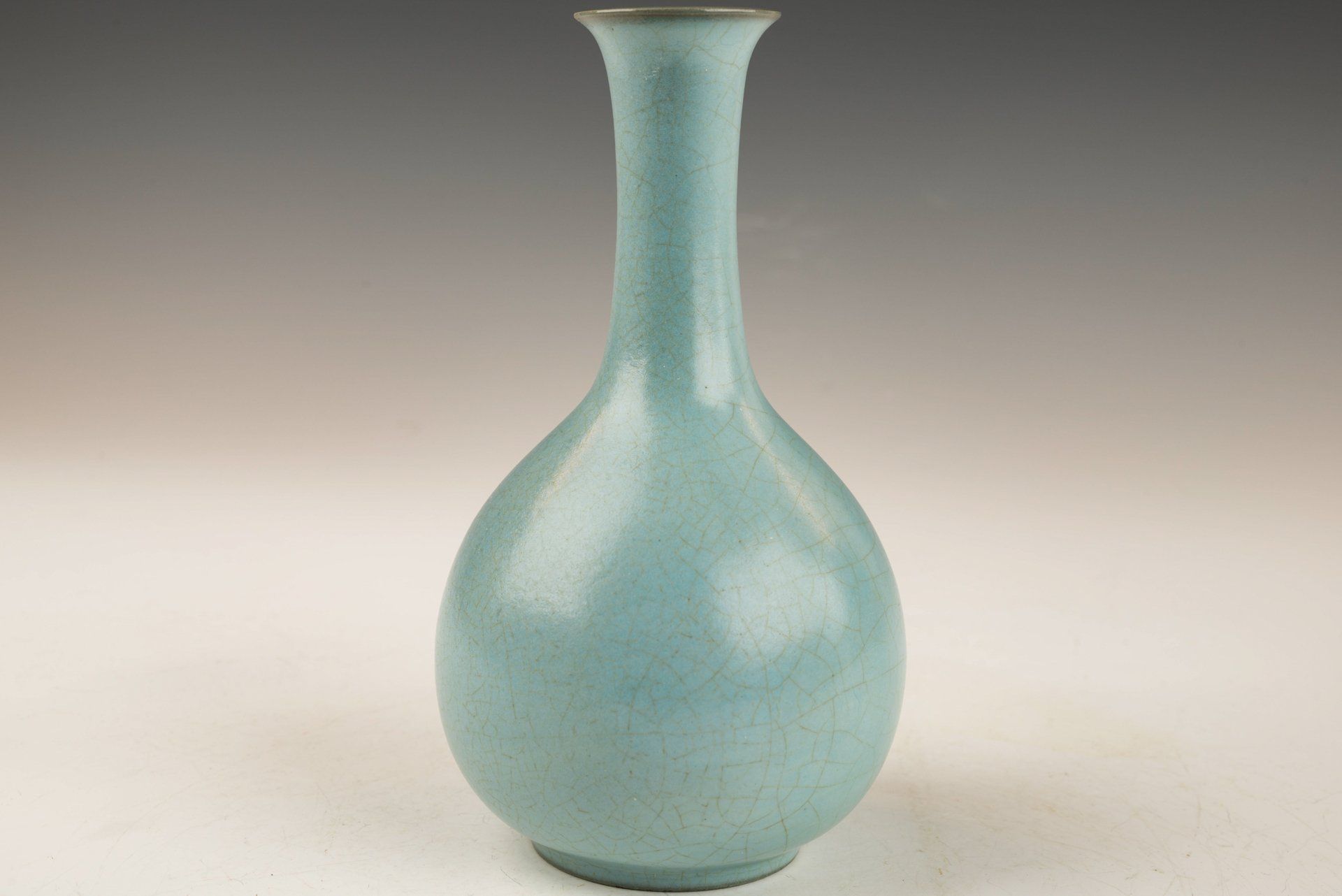

The first commissioned Royal Imperial Ru ware is thoroughly documented in historical texts, which indicate that Emperor Huizong instructed the Ru/ Ju Kiln to produce celadon wares characterized by modesty, understated elegance, and a deliberate simplicity that evokes a sense of antiquity. Notably, these initially commissioned Royal Imperial wares incorporated Rare Blue Crushed Agate into the glaze formulation. This can be discerned through the use of a 20x loupe, and microscopic photographs reveal the distinctive specks of agate found in each piece. The use of crushed agate is exclusive to the Official Royal Imperial Ru wares developed under Emperor Huizong's patronage. These early commissioned wares exhibit a variety of unique forms previously unseen, showcasing the remarkable skill and artistry of the Ru kiln artisans. The foot rings of all first official Ru wares remain unglazed. Additionally, each piece features a fine, cracked ice crackle in the glaze, with interior glazing also present. Many of these wares have marks inscribed on the bases, often inscribed, and the vases typically feature trumpet-shaped mouths, distinguished by their larger dimensions compared to merchant and tribute wares. The first commissioned Official Royal Imperial Ru wares are crafted from an ash-colored biscuit that transforms to brown upon firing. Furthermore, each piece exhibits the signature fine cracked ice crackle in the glaze, maintaining consistent interior glazing. Exclusively produced for the Emperor and his court, these wares reflect Emperor Huizong's appreciation for beauty in simplicity. He regarded each piece as an artwork, embracing any imperfections, which ultimately remained within the court as evidence of his vision's fulfillment. An illustrative close-up of a first commissioned Official Royal Imperial Ru vase depicts a droplet of glaze adhering to the foot ring, highlighting chips of Rare Blue Agate within the glaze. The accompanying ancient writings affirm the historical significance of these pieces as the legendary Official Royal Imperial wares commissioned by Emperor Huizong of the Song Dynasty. ppjrs

(click image to enlarge)

Ru Kiln Imperial Tribute Wares: Exceptional Artifacts Presented to Emperor Huizong of the Northern Song Dynasty, Featuring Right

Three Exemplary Tribute Vases.

Tribute ware is typically small, characterized by its fire-gilded copper bands, which exhibit corrosion patterns of cuprite and malachite. These distinctive features serve as reliable indicators of their age, often considered more authentic than thermoluminescence (TL) tests, earning the trust of experts in the field for authenticity verification. The production of tribute wares involves a glazing process that encompasses the entire surface. Notably, the pieces are fired on setters equipped with prongs to elevate the items above the kiln floor, resulting in spur marks on the base that are approximately the size and shape of sesame seeds. The glaze on tribute wares is smooth and showcases no inclusion of crushed agate in the glaze. It is important to note that the presence of crushed blue agate in the glaze is exclusive to Commissioned Official Royal Imperial wares. Typically, tribute wares feature either an off-white or ash-colored biscuit, representing the finest quality merchant wares that were adorned with fire-gilded copper bands and presented as tribute to Emperor Huizong. ppjrs

(click image to enlarge)

Sotheby's sold these two Flawed Northern Song Dynasty Ru Ware brush washers in Hong Kong. Now Christie's has sold a flawed Ru Ware Tea Bowl in Hong Kong. They should return the money

Second Commissioned Official Royal Imperial Ru-Wares Represent the Pinnacle of Celadon Production in China.

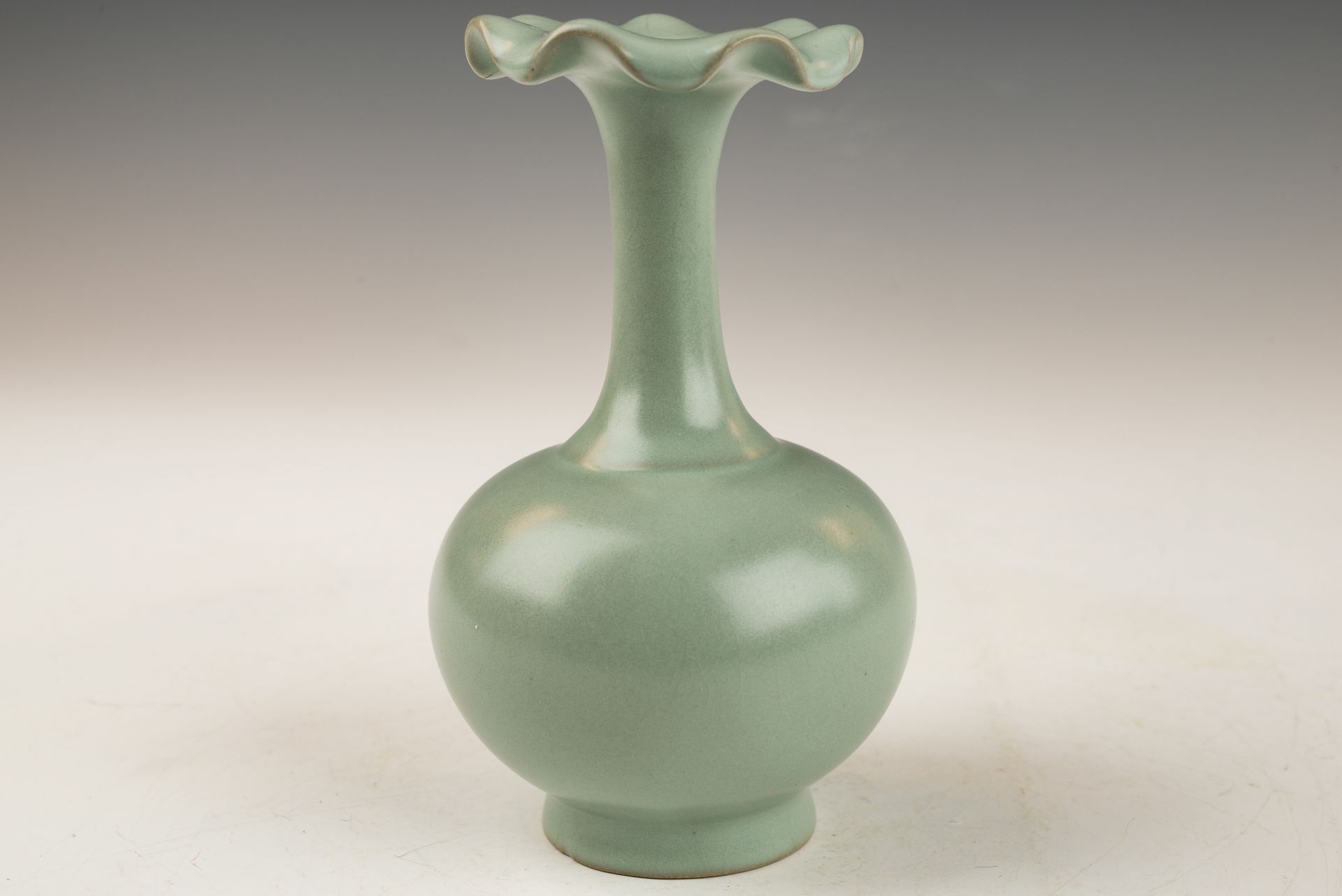

The Ru Kiln was commissioned to produce the exquisite second series of official Royal Imperial Celadon wares for Emperor Huizong and his court. These wares are characterized by their elegance, luxury, and aesthetic beauty, surpassing both merchant and tribute wares in refinement and size, while consistently showcasing a distinctive celadon hue. Notably, all pieces from this second series are infused with rare crushed blue agate within their glaze, an element observable through a 20x loupe, as evident in the microscopic photographs accompanying each piece. The use of crushed blue agate is exclusive to the Official Imperial Ru wares developed during Emperor Huizong’s reign. Furthermore, these second commissioned Royal Imperial wares exhibit a variety of unique forms that underscore the exceptional craftsmanship of the Ru kiln. The foot rings of these wares are unglazed and were intentionally fired flat within the kiln. Two vases feature fire gilding over copper bands exhibiting corrosion from cuprite and malachite, which serves as a reliable indicator of the artifact's age, more credible than thermoluminescence (TL) tests and widely acknowledged by experts to verify authenticity—an attribute that is impossible to replicate. It is important to note that all second-commissioned Royal Imperial wares are unmarked. They possess an off-white biscuit that transitions to a brownish tone post-firing. The wares exhibit a rich, smooth glaze with no crackling, while some pieces feature fire gilding over copper bands, and those without bands likewise maintain a flawless glaze. The vase displayed, adorned with a gilded silver band, shows minimal cracking, restricted to a few fine lines. The gilded silver band, exhibiting a darker celadon glaze enhanced with rare blue crushed agate, is visible under magnification. The fire gilding on silver bands has pores in the gild, allowing tarnish to seep through the pores, resulting in pronounced black corrosion on the bands. ppjrs

(click image to enlarge)

Ru-Kiln merchant wares are distinguished by their fine quality; however, they are primarily positioned in the market for affluent merchants, while items with imperfections are made available to the broader public at substantially lower prices.

The three Ru Kiln pieces displayed are examples of Merchant wares. Previously, the only known specimens of such wares were those collected by the Qianlong Emperor during the Qing Dynasty. However, following China's integration into the global market, numerous exquisite pieces and collections that had been concealed have now become accessible. Merchant wares are typically smaller than Commissioned Royal Imperial wares and exhibit complete glazing, including the foot ring. These items were fired using setters equipped with prongs, which elevated the pieces above the kiln floor. Consequently, they display spur marks that are approximately the size and shape of sesame seeds—distinctive traits that are exclusive to merchant and tribute wares. It is important to note that merchant wares lack the refinement of tribute wares, as the most exquisite examples were adorned with fire-gilded copper bands and presented to Emperor Huizong as tribute. ppjrs

(click image to enlarge)

Navigate Chinese Masterpieces Site Just Select Pages Below